“There comes a time when silence is betrayal.” — Martin Luther King Jr.

What happens to collective intelligence when a high-power individual doesn’t listen?

It crashes.

In the last article, we looked at research that showed that the higher people rise in status and power, the less able they are to consider other’s perspectives. This in turn reduces the collective intelligence of the groups they belong to, which is always sub-optimal. Sometimes it is disastrous.

In this article, I’ll introduce one strategy for addressing this challenge: teaching the less powerful to improve their perspective-giving skills.

Assertive statements

A challenge many teams face is getting the perspectives of the less powerful heard — and heard in such a way as to be taken seriously — by high-power and high-status people.

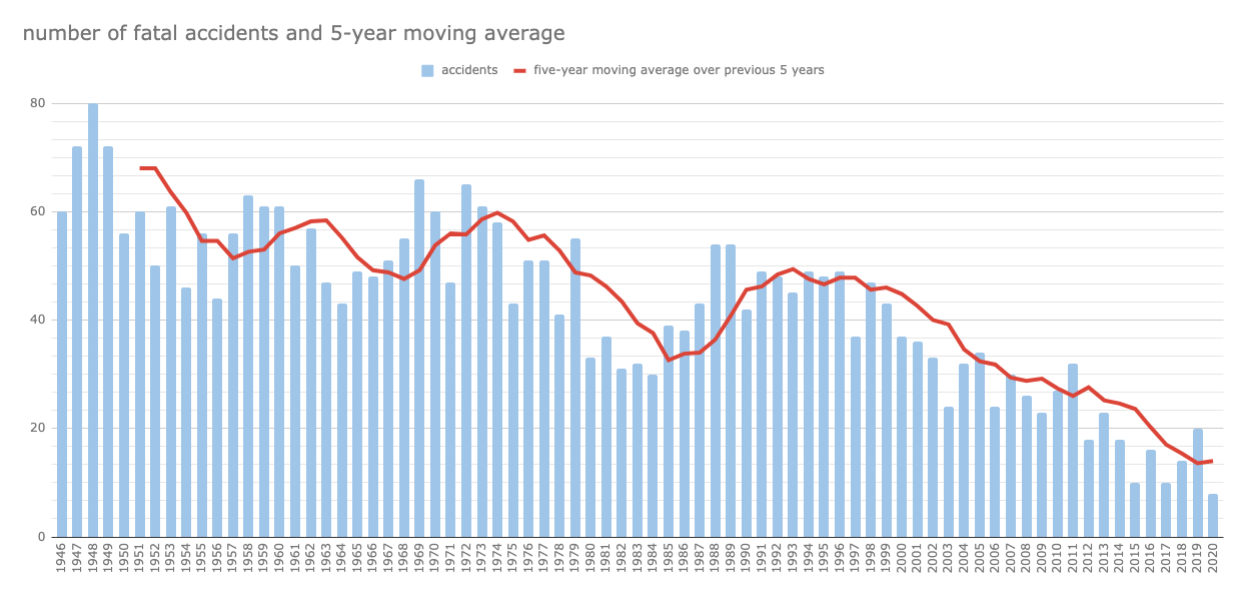

This exact problem was studied by the airline industry in the ’90s, which was dealing with scores of horrific disasters.

Graph: airline accidents and fatalities per year1

Upon detailed investigation, it was discovered that the cause of most airline crashes was not mechanical failures, but communication failures in the cockpit. First officers (co-pilots) and engineers were failing to speak up effectively, failing to get critical information into their pilot’s brains.

Within the hierarchal ‘Captain-is-King’ cockpit culture of the time, afraid of upsetting the captain, the crew would frequently mitigate their speech, sugarcoating important information, information that could have prevented a tragedy.

Malcolm Gladwell examined this phenomenon in his superb book, Outliers. Below he describes the mitigated speech between the first officer and the captain on the ill-fated Air Florida Flight 90 which plunged into the Potomac River, Washington, DC, shortly after takeoff, killing most on board.2

The first officer tried three times, ineffectively, to tell the captain that the plane had a dangerous amount of ice on its wings:

FIRST OFFICER: Look how the ice is just hanging on his, ah, back, back there, see that?

Then:

FIRST OFFICER: See all those icicles on the back there and everything?

And then:

FIRST OFFICER: Boy, this is a, this is a losing battle here on trying to de-ice those things, it gives you a false feeling of security, that’s all that does.

As they get clearance for takeoff, the first officer becomes only slightly more assertive:

FIRST OFFICER: Let’s check those wing tops again, since we’ve been setting here awhile.

CAPTAIN: I think we get to go here in a minute.

The last thing the first officer says to the captain, just before the plane plunges into the Potomac:

FIRST OFFICER: Larry, we’re going down, Larry …

CAPTAIN: I know it.

While obviously not as life-threatening, this type of communication failure occurs every day in most organisations. The less powerful mitigate to be polite, to avoid embarrassment, to avoid rocking the boat, to defer to ‘someone who knows better’, or just from shyness. In the absence of their perspectives, the collective intelligence of the team is diminished.

The airline industry successfully addressed the problem through Crew Resource Management (CRM) training. CRM aims to foster a culture where authority may be respectfully questioned.

To train the crew to speak up, consultant Todd Bishop developed a five-step assertive statement process:

Opening or attention-getter - Address the individual: "Hey Chief," or "Captain Smith," or "Bob," or whatever name or title will get the person's attention.

State your concern - Express your analysis of the situation in a direct manner while owning your emotions about it. "I'm concerned that we may not have enough fuel to fly around this storm system," or "I'm worried that the roof might collapse."

State the problem as you see it - "We're showing only 40 minutes of fuel left," or "This building has a lightweight steel truss roof, and we may have fire extension into the roof structure."

State a solution - "Let's divert to another airport and refuel," or "I think we should pull some tiles and take a look with the thermal imaging camera before we commit crews inside."

Obtain agreement (or buy-in) - "Does that sound good to you, Captain?"

Teaching this simple assertiveness technique (alongside some related theory)3, dramatically improved cockpit communications and was instrumental in preventing numerous disasters. It is an easily taught skill.

Leap before you look

Joseph Grenny, the co-author of Crucial Conversations, also offers some sound advice about speaking up:

“the best way to build a habit of speaking up is to leap before you look, speak before you think”

He claims that 90% of our anxiety about speaking up is pure imagination, that we dream up horrible scenarios that artificially raise the stakes of simple conversations. We imagine the other party getting angry, or ignoring us, or dismissing our input; outcomes that rarely eventuate if we speak up with kindness, clarity, and confidence.

By just launching into speech, as long as intentions are sincere and not aggressive, the other party is usually receptive4. Some rehearsed phrases can help. E.g., “Hey Bill, I’m a bit concerned if we proceed this way then …” (the first part of an assertive statement to get the tongue moving).

It can be nerve-racking at first but gets much easier with practice.

Speaking up is a critical collaboration skill. It can be learned, and should be learned, by everyone involved with collaborative work. Otherwise, important perspectives will not get heard.

It is, however, not the only strategy required to optimise collaboration. Leadership attitudes and organisational culture are also important. We’ll look at these in future articles.

Learn More

More about CRM can be found here: International Association of Fire Chiefs (2003). "Crew Resource Management: A positive change for the fire service" (PDF)

To learn to speak up in difficult situations, Crucial Conversations offers excellent guidance. It is one of the texts I recommend in cultural development work.

More resources on speaking up: How Do I Say That

Image Credit

Cockpit via Jonny Belvedere

Source: Aviation Safety Network

Gladwell, Malcolm, (2008). Outliers: the story of success. New York. Little, Brown and Company

See International Association of Fire Chiefs (2003). "Crew Resource Management: A positive change for the fire service"

Dealing with highly dominating, narcissistic, or abusive people takes particularly good skills, which we will look at in future articles.

John wrote "Teaching this simple assertiveness technique (alongside some related theory)3, dramatically improved cockpit communications and was instrumental in preventing numerous disasters. It is an easily taught skill."

The recognition that this approach can be taught, learned and practiced is crucial, as so many think it not a learnable behavior, it just something that some (other) people are naturally good at. It looks like you will have a future post about the 'other' side of the conversation, since the leader must also learn a new skill.