“Most conduct is guided by norms rather than by laws. Norms are voluntary and are effective because they are enforced by peer pressure.”― Paul Collier

Organisational norms can be frustratingly tenacious. No matter how hard we try to change destructive patterns of behaviour, they often persist in spite of the multiple interventions we throw at them.

A management consultant friend recently shared the following anecdote that serves as an excellent case study for discussing the problem of norm persistence.

Case Study: inter-divisional sabotage

Within a multinational corporation, there were two waring divisions: operations and a particular sales department. The genesis of the animosity was unknown but both departments had normalised childish and uncooperative behaviour. The sales department would book customer orders knowing all too well that operations could not possibly meet the delivery date, and then take great delight in criticising them for being ‘tardy’. In retaliation, operations would regularly de-prioritise that particular division’s orders and took delight at telling them to ‘please wait patiently in the queue’.

The situation become untenable, customers were complaining, business was being lost, and brand damage was occurring. Although senior leadership had frequently requested that the two departments sort out their differences, the pattern of behaviour was entrenched. HR was requested to intervene.

The first intervention they made was to adjust the bonus scheme to reward combined performance over divisional performance. No difference. Individuals persisted in the behaviour even though they were being financially punished for it.

The second intervention was to introduce collaboration into each individual’s performance review. All they had to do was show evidence of interdepartmental collaboration to achieve 25% of their points. Still no difference. Departmental rivalry trumped positive performance reviews.

Finally, out of desperation, the organisation performed what Laurence J. Peter and Raymond Hull referred to as a percussive sublimation.1 The two department heads were kicked upstairs to allow fresh blood to take over. But that was as futile as chopping a couple of heads off Hydra. The new promotees simply ‘regenerated their bosses’ heads’, duplicated their behaviours, and the norm thrived.

Norm persistence and work avoidance

The anecdote is a classic case of work avoidance. Work avoidance is something we all do: we often default to norms of behaviour, even if they hurt us, or others, rather than undertaking the hard work of change. Change takes energy. Defaulting to norms is easy.

When an in-group reinforces a particular norm, it becomes ever-harder for the individuals in the group to change. Smokers socially support other smokers, for example.2

In our anecdote, the members of the respective in-groups reinforced the norm of sabotaging the other division. No doubt there were significant social rewards for doing so. There would have been approval signals: little smiles, little nods, little gestures that said “well-done buddy, you got ‘em this time”. Such signals trigger a rush of dopamine and bestow a sense of belonging and inclusion to a group — a huge primal motivator. Social inclusion rewards are enormously powerful, and easily overrule extrinsic incentives and structural mechanisms like those the HR department attempted.

In order to change the norm, the stakeholders, those individuals that had psychological stakes in the rewards of sabotage, needed to change their behaviour, en masse.

Challenges like these require significant leadership involvement. Superficial interventions will have little effect on deep-rooted norms.

A senior leader or skilled facilitator should have brought the key stakeholders together and set up an environment where they, the stakeholders, worked the problem until a solution was found. Now, this is no easy task. It takes skill, discipline and perseverance, but it can be done.

Pressure cooking stakeholders

Eminent leadership scholars, Ronald Heifetz, Marty Linsky, and Alexander Grashow argue that the best way to address difficult challenges like this is to steer the stakeholders into a productive zone of disequilibrium,3 where they confront their responsibilities beyond current norms and petty grievances, with all the discomfort that process entails.

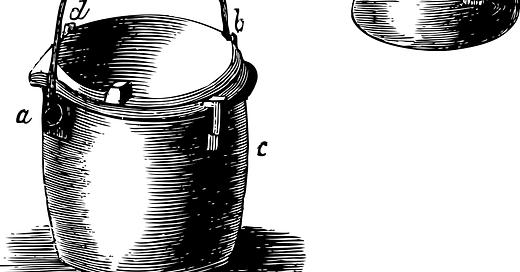

They use a metaphor of a pressure cooker to describe the process of taking people out of their comfort zone by turning up the heat, but not by too much:

Set the temperature and pressure too low and you stand no chance of transforming the ingredients in the cooker into a good meal. Set the temperature and pressure too high and the cover will blow off the cooker’s top, releasing the ingredients of your meal across the room. It helps to think of yourself as keeping your hand on the thermostat, carefully controlling how much heat and pressure is applied.

This is how it might play out in our case study:

Firstly, the challenge needs to be put to the stakeholders in very clear and unambiguous terms, for example: “Collaboration between your two departments is clearly broken. You are letting our customers down, it is costing us business and it is damaging our brand. How can you resolve this conflict once and for all and establish harmonious collaboration from here on in?”

At this point, the leader shuts up. He or she does not offer any suggestions, but rather makes it clear that he or she is going to patiently wait for as long as necessary for the stakeholders to engage in meaningful dialogue with each other. If the stakeholders look to the leader for guidance — “what do you suggest we do?” type questions — the leader refuses to answer. The leader might simply remain silent, or say something like: “you have created this problem between yourselves, so the solution must come from you. It can not come from me or anybody else”.

By making it very clear that the stakeholders, and only the stakeholders, are to find a solution, it pushes all of the work onto the stakeholders. In Heifetz’s metaphor, this is ‘turning up the heat’.

At this point, the stakeholders may start blaming each other and airing all sorts of grievances. The leader’s job now is to maintain a safe ’holding environment’, allowing the conflict to air but trying to regulate the temperature so the situation doesn’t explode. He or she might do this by calling time out, or asking people to be civil to each other, saying something like, “let’s cool this down a bit. There is no need for ad hominem attacks. Let’s focus on systemic issues, not individuals”. In Heifetz’s metaphor, this is ‘releasing the pressure valve’.

As mentioned, it is human nature to avoid work. The stakeholders might try to squirm out of it by coming up with some sort of superficial solution, agreeing on anything just to get out of the room (i.e., the dotted work avoidance line). At this point, the leader turns up the heat again by challenging them and asking conflictual questions. For example, he or she may say something like, “you haven’t addressed the elephant in the room yet, you haven’t spoken about why the desire to engage in rivalry is more important to each of you than doing the right thing by the customer”.

The leader is trying to destabilise the equilibrium, to surface the normative patterns that are holding the negative behaviours in place, to force the stakeholders to face these patterns, address them, and eventually enable a phase transition to occur and a workable solution to emerge.

This process of turning up the heat and releasing pressure might go on for a long time, it might take several sittings and span weeks or months. It stops only when a coherent solution comes from the stakeholders.

This type of leadership approach is a 180º shift from traditional leadership paradigms where a leader is supposed to come up with solutions and pass them down to passive stakeholders. It is a crucial skill for today’s world where the collective intelligence of organisations, the ability of teams to initiate their own ‘pressure cooking’ and tackle difficult challenges with autonomy, will largely determine an organisation’s success.

Image Credits

Pressure Cooker via Pixabay

Productive Zone of Disequilibrium — my slides, adapted from Heifetz et al, 2009

Peter, Laurence J, and Raymond Hull. The Peter Principle. New York: Bantam, 1970

Yun, E.H., Kang, Y.H., Lim, M.K. et al. The role of social support and social networks in smoking behavior among middle and older aged people in rural areas of South Korea: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 10, 78 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-78

Heifetz, R., Grashow, A. and Linsky, M. 2009, 'The Practice of Adaptive Leadership: Tools and Tactics for Changing Your Organization and the World', Harvard Business Press